I’ve recently been working on this lovely bracket clock by James McCabe. It was brought to me because of a problem with the striking mechanism - when wound the clock would strike continuously until it ran out of power. There are a number of things that could cause this but it was agreed that the clock would also be serviced while it was in the workshop, as it was evident that there was a lot of very dark oil and wear which could be seen simply by looking at the backplate.

Another obvious issue before a full diagnosis was some screws missing from the brackets which would be replaced. Finally, the case needed some repair work: there was a dent on the back and obvious uses of filler from a previous poor quality repair which would be rectified.

Clock Diagnosis

Disassembling the clock made it clear it had not been treated well by the previous repairer. Plates were held together by old nails, and parts of the under-dial work had bits of wire wrapped around them to secure them in place. You can also see that the teeth of the great wheel are flooded with oil. No clock needs this amount of oil, and it certainly shouldn’t be here. There was also a large amount of wear and tear on the pivots and pivot holes throughout the clock which I will address later.

Finally, now the dial is off the cause of the issue with the striking mechanism can be seen - the tail of the gathering pallet has broken off and is missing. This would normally come to rest on a pin on the rack and arrest the striking train after the appropriate number of ‘dings’, without the tail there’s nothing to stop the train and the clock will strike until there is no more power. A new one will need to be made.

Service and overhaul

A core part of any clock repair is a service or overhaul. At it’s most basic, this means two core things: cleaning all of the components thoroughly to remove old oil, dirt and dust, and addressing mechanical wear and tear.

Pivot Polishing

Below I have illustrated wear to pivots being corrected. Side by side you can see how different polished pivots look and the poor condition they were in previously. Without polishing, the friction from the pivot is greatly increased and can cause the clock to stop. The pivot must be free from scores or defects, and be perfectly parallel to allow the wheel to turn as freely as possible. The condition of clock pivots can vary wildly, but generally a clock will benefit from having all pivots polished at least a little.

Clock Plate Bushing

The other main point of wear is the holes in which pivots sit. The steel pivots wear away the brass plate which results in oval holes; this changes the distance between the wheels and pinions, known as depthing, and affects the efficiency of power transfer and in the worst cases can cause the train to jam. To fix this, a new brass bushing is added to the clock. When I bush a plate, I use the smallest bush possible as this makes it almost invisible once the repair is completed. You can see in the before image the gap to the left, and the large size of a previously fitted bush. On the right after repair the new hole is round, holds the wheel in exactly the right place without too much ‘side shake’, and is almost invisible to the naked eye.

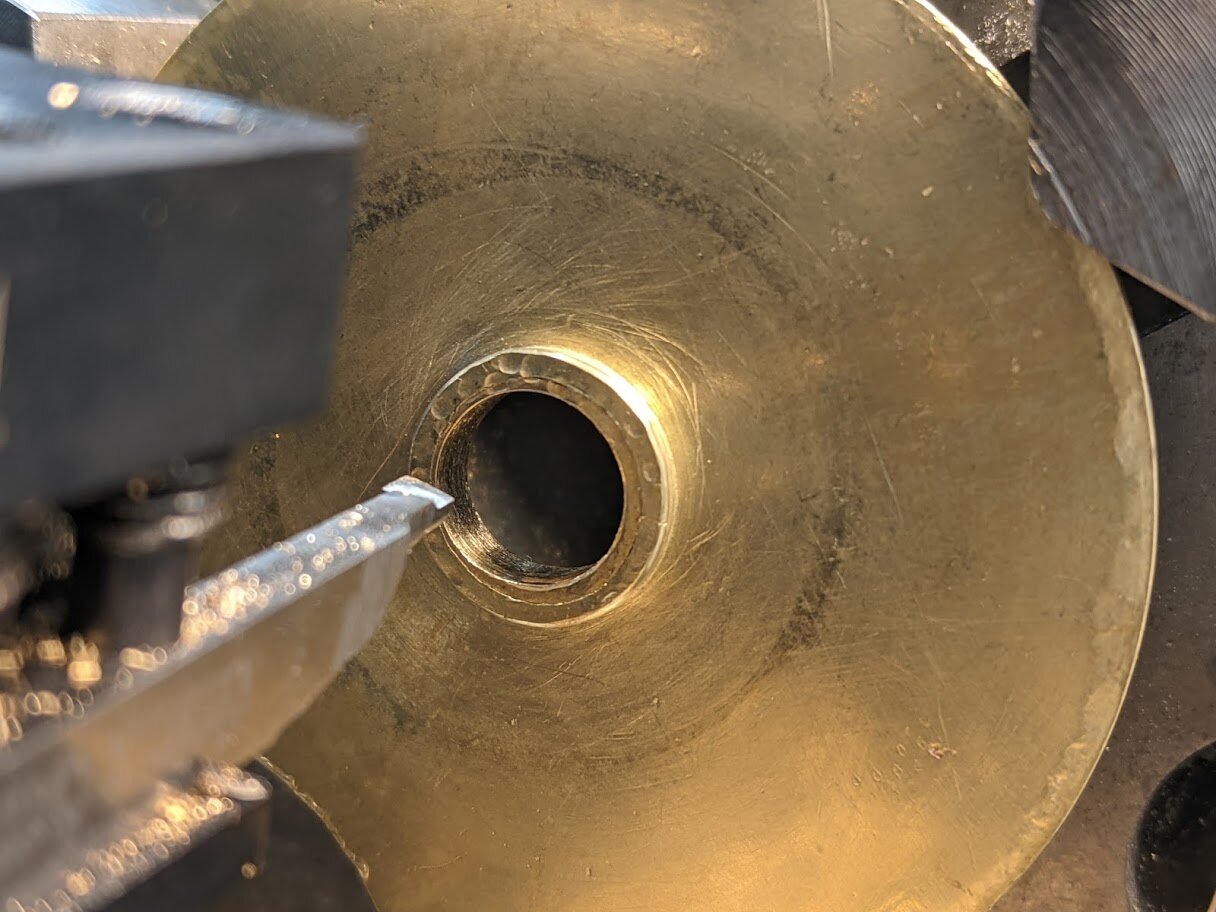

Barrel Bushing

Part of the clock which seemed to have been neglected for some time was the barrel bearing: where it rotates about its arbor. This is a large bearing, and very difficult to repair without the correct equipment, which is perhaps why it has not been repaired before. A custom bushing was made and riveted in place before adjusting to the correct shape and size on the Schaublin lathe.

You can see hammer marks on the barrel which is from previous, insufficient and poor quality repairs. An alternative to a proper bushing is to hammer what metal remains in order to fill the gap. This is impossible to do accurately and only makes the remaining metal thinner, which in turn speeds up future wear. In my workshop if something needs to be repaired, it will be repaired properly.

Component Manufacture

As well as replacing the damaged gathering pallet, it was found that some screws were missing from the clock: the case brackets were being held in place by one screw each rather than the correct two, so new screws would need to be made to match the originals.

Gathering Pallet

A gathering pallet is a very complex part with a large number of important dimensions. For this reason, I elect to use my CAD/CAM facilities to quickly produce an accurate part based on several key measurements. The 5-axis machine I use allows quick prototypes made from brass to be made to confirm all measurements are correct before a final part is made from steel then hand-finished, hardened, tempered, and polished the traditional way. Combining cutting edge technology with traditional hand skills in this way cuts out a lot of trial and error that can often be required in clock repair.

Making Clock Screws

A pair of screws needed to be made to match those already in the clock. After measurements of the old ones were taken, the new ones were made, mostly on the lathe, from silver steel. They were then heat-treated to be hardened and tempered before finishing with a satin polish to match the old ones.

Here you can see the two new ones with the two originals, can you tell which are which? When making parts for clocks it is important to choose the correct method to ensure the new components look correct. In the original parts the slots would have been cut by hand, and so I did the same here. Slots can easily be machined, but these would have made the screws look too modern and out of place.

Finally, after all the work is completed, the clock can be reassembled and oiled throughout before testing for 2-3 weeks. Once I am confident everything with the movement is as good as it can be, the clock is ready to be returned to the owner.